What is the essence of the concept of good? “Perfect good for man. Public and private

Good

good(Greek άγαθον, lat. bonum, fr. bien, German Gut, English good) is a concept that has long occupied philosophers and thinkers, playing a vital role in the public, economic and social sphere, and therefore included in the sphere of public policy, causing certain aspirations and activities of the political union - the state.

I) Understanding by good in a broad sense, the satisfaction of a human need or aspiration, and therefore the goal of each aspiration, the thinkers of the ancient classical world (Plato, Aristotle and many different schools that developed their teachings) explained: firstly, that the very understanding of good is subjective, and therefore the aspirations of people very different; secondly, that, nevertheless, every good is a goal to achieve which is human aspiration, activity, human enterprise; thirdly, that, despite the subjective understanding, human goods in general can be represented by three categories:

1) material benefits, the achievement of which gives a person sensual pleasure and pleasure; 2) spiritual benefits - understanding of beauty and truth, delivering spiritual pleasure and satisfaction to a person’s rational aspirations; 3) peace of mind, born from the consciousness of fulfilling a duty, is a moral good, virtue; 4) the highest good - εύδαιμονία, well-being (see this next), which consists in achieving all the benefits that a person strives for, is the most important goal of human life, which corresponds to the highest political activity, possible only in the state, why the ancient thinkers and was seen as a means to achieving well-being.

The Christian religion has significantly expanded views on the good, greatly raising man's ideas about the goals and objectives of human aspirations. Christ's great sermon about all-forgiving Christian love and love for one's neighbor radically changes the idea of good: good is no longer only the satisfaction of one's own interests and benefits, but also the delivery of benefits to others. The principle of egoism, which had dominated until then, is placed next to the new, firmly and majestically established principle of altruism: not only one’s own good, but also the good of another constitutes the real good of a person. The lofty Christian teaching about brotherhood and brotherly love is only gradually becoming the property of humanity. A long period of barbarism and distorting interpreters moved humanity away from the correct understanding of the concept of all-round good indicated by Christianity. But the closer we get to our time, the more this simple yet majestic truth about altruism, which strives to constantly moderate egoism and can lead forward, to a new flourishing, all types and forms of human unity, grows.

When, after medieval oppression and grave misunderstandings, thirsty thoughts turned to the works of ancient thinkers, the ethics of the latter, their views on good and well-being, had a charming effect for the first time, and in the 16th and 17th centuries. a number of eudaimonic theories(see this next), who explained and interpreted more or less successfully the teachings of Aristotle and continued his school. But there also came criticism of the views on the state as a means to ensure well-being, and at the same time criticism of the views on the good. Something new compared to philosophers imitating the ancients, says the famous Bacon(see this next):

Ethics, which must analyze in a positive way the manner of action of the human will, indicates the ideals of good and the way in which a person can achieve it. The ideal of good follows from the twofold natural desire of man: to become an independent person and, moreover, to become a particle of some large (social) whole; the first constitutes a private good, the second a public good. The thinker of the 17th century showed a particular breadth of views in the field of studying the principles of ethics. Locke(see this next), who cleared the paradoxical teaching of Hobbes (see this next) about egoism and became the favorite teacher of the English. Arguing about the good, he considers the pursuit of happiness to be the moral principle of human activity and completely defeats Hobbes, who believed that in a state of nature a person has the opportunity to act completely according to his own will, and in a state a person can act and strive only in complete obedience. Locke argues that both in the state of nature and in the state, man enjoys and should enjoy freedom, limited only by the good of others. These ideas of his were developed by many English people. thinkers in so-called systems goodwill. I came to approximately the same conclusions earlier Descartes, from whose ideas came the interpretations of Pufendorf and Thomasius. Ethics had a particularly strong influence on German scientists by explaining altruism as a person’s love for his neighbors as a result of his love for God. Spinoza(see this next). French thinkers of the late 18th century, who prepared the ground for the theory of utilitarianism, which he so brilliantly developed Bentham(see this next), which set the goal of the state as great happiness for the greatest possible number of people, and the critical philosophy of Kant, which clarified the legal tasks of the state, led thinkers of the 19th century. to views, although differing in details regarding good and well-being, but increasingly approaching the correct understanding of the Gospel teaching about good, which consists in Christian love for one’s neighbor.

II. In economic and social terms, a good means everything that, having value, can have a market price, therefore, in a broad sense, all property benefits are understood. In German Gut and in French bien They also have the special meaning of real estate. Property benefits are created, acquired, changed, distributed on the basis of internal ones that govern economic life economic laws, studied political economy. The acquisition of values or things, both individual and the totality of such property benefits, property, affects the social status of each person, gives rise to various social classes, depending on the amount of property benefits that each person achieves and uses. The difference between such classes, their mutual relationship and mutual influence, the transition of people from one class to another in connection with the creation of various kinds of human unities, the movement of property goods and the movement of the classes themselves, ascending and descending, occurs on the basis of internal, social, or social laws studied sociology, or social science(see this next).

III. The quantity of all kinds of goods and methods of distributing them among members of the society constituting a political union - state, predetermines the power and political significance of the latter. Therefore, the task of the state and the subject of its special political or police activities (see this next) should be the creation of such general and identical conditions for all under which the legitimate aspirations of citizens to achieve benefits would be possible for everyone. Such state activity is based on the ability to harmonize the norms of positive law with the requirement of the natural law of development and the laws of economic and social. The methods of such an agreement and the reasons for the different achievements of such a political goal by different states are being studied by science."

What goods does a person need?

Once you cross the border, the pleasant becomes disgusting. Democritus, ancient Greek scientist

After reading, you will find out:

- ? How human needs are satisfied.

- ? What is the role of nature in meeting your needs.

- ? How does social production provide you with everything you need?

- ? What are the differences in the goods that satisfy your needs for food and education.

- ? can the same need be satisfied in different ways?

- ? Is there a specific connection between the things that satisfy your needs?

From the previous topic you already know that in order to live, a person must satisfy a variety of needs. What does she need for this?

What are goods and which of them satisfy our needs? Feeling thirsty, you drink tea, coffee, water. When you're cold, you put on warm clothes. Economists say: “Everything that satisfies our needs is a good.” He takes part of the benefits necessary for human life from nature. This air and sun rays, sources of water and ponds, wild berries and nuts, mushrooms and fish, flowers and medicinal plants. All of these are free benefits.

People do not create free goods, but find them in nature in a ready-to-use form. The free nature of such goods is relative. It only means that these benefits are not the product of human work, but are obtained from nature. Under certain unfavorable conditions in society, the number of so-called free goods increases, they become paid for by the user (drinking water, medicinal plants, land, clean air, etc.).

However, man needs significantly more benefits than nature can provide. Therefore, people learned to extract and create the goods they needed. So, those benefits that a person specifically creates and produces in order to satisfy his needs are called economic. Looking at the things you use in life, you will agree that they are all produced in different plants and factories to meet your needs. These are the economic benefits you need in life. Examples of economic goods include a car, a TV, skis, a pen, a bicycle.

Economic goods differ from free goods in that they are the result of conscious human work aimed at producing certain goods to satisfy certain needs. Therefore, economic benefits are always quantitatively limited. The creation of economic benefits is carried out consciously, i.e. according to the previous idea or plan. The process of human creation of goods differs from the instinctive actions of bees, which create cells from wax, or beavers, which build dams, in that human actions are aimed at realizing a predetermined goal.

And in the end, to create economic goods, a person must use other goods. After all, your sweater is knitted from wool, and your shoes are made from leather.

Nowadays, humanity produces tens of millions of economic goods, and all of them, just like free goods, are assigned to satisfy human needs.

The economic benefits that people enjoy are very diverse. Some of them can be used for many years (furniture, refrigerator, car). Such economic benefits are called long-lasting, i.e. durable items.

A person uses other economic benefits only once. These are short-term economic goods (for example, bread, sugar, ham, ice cream). The famous cartoon character Winnie the Pooh argued that honey is a thing that is there and then immediately gone.

Thus, the criterion for dividing economic benefits into long-term and short-term is the period of their use by a person. A number of services are also interchangeable. For example, transportation of goods and passengers can be carried out using locomotives, trains or cars. In addition, there are goods that can satisfy human needs only in combination. This is a car and gasoline, skis and ski boots, a camera and film. Such goods are called complementary (or complementary).

So, in order to live, a person must satisfy his needs with a variety of goods. A person takes part of the necessary benefits from nature, and most of them he produces consciously. What does a person need to create these benefits? You will learn about this in the next topic.

Let's do it again

- Goods are everything that satisfies our needs. There are benefits:

- Free goods are goods that people do not create themselves, but take from nature.

- Economic goods are goods that a person specifically creates and produces to satisfy his needs.

Economic benefits, depending on the period of use, are divided into long-term and short-term.

- Long-lasting economic benefits are benefits that a person grew up with and enjoys for a long time.

- Short-term economic benefits are benefits that a person produces and uses immediately.

Economic benefits are divided into goods and services.

- Goods are economic goods that take material form

- Services are economic goods that are provided in the form of useful activities or services.

Goods and services can be complementary and interchangeable.

- Interchangeable (substitute) goods are goods and services that can satisfy the same human need.

- Complementary goods are goods and services that can satisfy a certain human need in a complex.

check yourself

1. Which list contains only free benefits:

- a) Coca-Cola, dress, skis;

- b) beer, tape recorder, dishes;

- c) brushwood, minerals, sun;

- d) paper, rubber, car.

- Which list contains the exact economic benefits:

- a) doctor’s services, firewood, air;

- b) computer, nuts, pasta;

- c) cigarettes, heat, books;

- d) oil, machine, Coca-Cola.

- What distinguishes services from goods:

- a) rarity;

- b) the ability to satisfy human needs;

- c) intangibility;

- d) benefit.

Give an answer to the question

1. What is the connection between needs and goods?

2. How can we define the concept of “good”?

3. What goods are always quantitatively limited?

4. What do a product and a service have in common?

5. What is the difference between a product and a service?

6. What goods can be called complementary?

1. Can free benefits turn into economic ones?

2. The same human need can be satisfied by a variety of economic benefits. Is any economic good capable of satisfying the diverse needs of people? If so, give examples. If not, justify your answer.

3. What property of needs is associated with the fact that goods can be interchangeable?

Question for discussion

1. Are there certain limits to a person’s use of economic goods?

2. A person cannot put on several pairs of shoes or suits at once. Why then do all countries strive to increase the production of goods and are proud of the fact that per capita of their country they produce more goods than others?

Advice for a business person

- Renew the range of products that are produced. Remember that you should not only develop the right product, but also create a new one that can satisfy the same need, but at the highest level.

- Study competitors' products, because they satisfy the same human need as yours.

- Study substitute products that, once on the market, can “take away” your consumer.

GOOD 2, union. Razg. Moreover; thanks to. The dogs climbed far into their kennels, fortunately there was no one to bark at. I. Goncharov, Oblomov. We tried to collect as much firewood as there was no shortage of it here. Arsenyev, Dersu Uzala. Straight from the airfield I went to Sadovaya, --- to Korablev, - fortunately, all my luggage was a small suitcase. Kaverin, Two captains.

GOOD 1, -A, Wed

1. Well-being, happiness, goodness. For the good of the Motherland. □ - He only deserves the name of a person who sacrifices his personality to the common good. Turgenev, Rudin. - This is not my personal matter, but a question of the common good. L. Tolstoy, Anna Karenina.

2. pl. h. (benefits, good) what or which. That which serves to satisfy smb. human needs, provides material wealth, and gives pleasure. Production of material goods. □ [Pertsov:] So today I went to Maryina Roshcha to enjoy the benefits of nature. A. Ostrovsky, Hard days. You get so busy during the day that you can barely drag yourself to the bivouac. A tent, a fire and a warm blanket then seem to be the best blessings that have been given to people on earth. Arsenyev, In the Ussuri taiga.

3. usually to whom, meaning tale (usually combined with a subordinate clause). Very good, happiness. It is fortunate for Ivan Fomich that he is settling in the village only temporarily. Saltykov-Shchedrin, Little things in life. Good for those who will wash their troubled soul here to the very bottom. Zabolotsky, Washing clothes.

All the best- a farewell wish. For no good- for nothing, under no circumstances.Source (printed version): Dictionary of the Russian language: In 4 volumes / RAS, Institute of Linguistics. research; Ed. A. P. Evgenieva. - 4th ed., erased. - M.: Rus. language; Polygraph resources, 1999; (electronic version):

Any means that satisfies human needs is good. To fulfill this function, goods must have utility. Utility is the suitability of an object to serve the satisfaction of human needs. Ignorance of the useful properties of things excludes them from the composition of goods. For example, coalXVIIIcenturies was practically not used in the economy and, therefore, was not a benefit.

The usefulness of goods can manifest itself in both material and intangible forms. Thus, potatoes on our dinner table are a purely material thing, while at the same time books, newspapers, and television bring us benefits of an intangible nature.

The benefits used by humans are divided into economic and non-economic. Economic goods include benefits, the possibilities of obtaining which in relation to human demands are limited. In other words, economic goods are rare.

Non-economic goods are present in the world around us in unlimited quantities. Therefore, their needs are fully satisfied. These include freely reproduced natural goods: air, light, water.

Non-economic benefits become economic if there is either an increase in the need for them or a reduction in the sources of their supply. For example, water flowing from a spring in the forest is a non-economic good. The water supplied to our apartment through the water supply is an economic benefit, since its quantity is limited in relation to our needs.

With regard to economic goods, the problem of determining their value is of fundamental importance. At one time, A. Smith formulated the famous paradox about diamond and water. “There is nothing more useful than water,” Smith noted, “but almost nothing can be bought with it, almost nothing can be obtained in exchange for it. On the contrary, a diamond has almost no use value, but often a very large quantity of goods can be obtained in exchange for it.” The resolution of the paradox was given within the framework of the Austrian economic school. In their opinion, the value of goods directly depends on their rarity in relation to human needs.

Economic benefits are divided into tangible and intangible. In turn, material goods are divided into consumer goods (direct goods), means of production (indirect or production goods) and services.

Direct benefits go to the final consumer (the population) directly in the form of food, clothing, shoes, etc. There are short-term consumer goods, the service life of which is less than a year (for example, food, medicine, this also includes clothing) and durable goods (furniture, cars, televisions, etc.).

Indirect benefits mediate the process of obtaining consumer goods. They are necessary not for their own sake, but for the sake of consumer goods that are produced with their help. According to the method of participation in the production process, they are divided into two groups:

1. Instruments of labor that are used repeatedly in the production process and do not become part of the finished product. This includes buildings, machinery, equipment.

2. Raw materials and materials that are fully used in one production act and become part of the finished product (iron ore in the production of iron and steel, materials in the manufacture of clothing, etc.).

Between production and consumption there is a sphere of material services. It provides, for example, the transportation of produced goods from producers to consumers, storage, packaging, sale of products, etc.

Intangible benefits are associated with the satisfaction of human social and spiritual needs. They are divided into internal and external. Internal intangible benefits include the entire set of physical, moral, cultural, business and professional data of a person. In other words, internal intangible benefits are, first of all, the spiritual baggage that every person has.

External intangible benefits include benefits that other people provide to a given person in intangible form (services of a lawyer, teacher, priest, etc.).

In addition, economic benefits can be classified according to forms of consumption into individual and club (public).

Human good is individual and at the same time social, and we must now outline the way in which these two aspects are combined with each other. We will do this by selecting eighteen terms and gradually linking them together.

Social goals Ultimate goals

cooperation private good

institution, role, improvement task

Personal Internal

relationship value

Our eighteen terms refer to: 1) individuals, their capabilities and actions; 2) interacting groups; 3) goals. Triple division of goals allows for triple division in other categories, which leads to the following scheme.

action Development, skill

Individual goals Potentiality Relevance

Ability, need

Plasticity, ability to improve, freedom

Orientation, revision

First, we link together the four terms from the first line: ability, agency, private good, and need. So, individuals have the ability to act. By acting, they provide themselves with moments of private good. The moment of private good here is understood as any existing thing, be it an object or an act, that meets the needs of a particular individual in a given place and at a given time. Needs must be understood in the broadest sense, not limiting them to vital needs, but, on the contrary, expanding them and including all kinds of desires.

Second, the four terms in the third column are linked together: collaboration, institution, role, and task. In fact, individuals live in groups. Their operation is, to a large extent, cooperation. From this follows a certain established pattern, fixed by the role to be performed or the task to be solved within a certain institutional framework. These frameworks are family and morals, society and education, state and law, economics and technology, Church or sect. They form a generally recognized and universally accepted basis and method of cooperation. As a rule, they change very slowly, since change, as opposed to collapse, implies a new common understanding and a new common agreement.

Thirdly, the remaining terms from the second line should be connected with each other: plasticity, ability to improve, development, skill and well-being. Thus, individuals' abilities to act, being malleable and susceptible to improvement, allow for the development of skills, namely, the very skills that are necessary for the fulfillment of institutional roles and tasks. But, in addition to the institutional basis of cooperation, there is also a concrete way of expressing cooperation. The same economic structure is compatible with prosperity and recession. The same constitutional and legal provisions allow for a wide range of differences in political life and in the administration of justice. Similar marriage and family rules in some cases bring happiness to the house, and in others - misfortune.

This particular way in which cooperation expresses itself is what is meant by well-being. This good is distinct from aspects of private good, but is not separate from them. With all this, it does not mean them separately, in their correlation with the individuals whom they satisfy, but in aggregate and repetition. My lunch today serves as a moment of private benefit for me; but a daily lunch for all members of the group receiving it forms part of the welfare. In the same way, my education is a private good for me; but for anyone who wants to receive it, education is part of the well-being.

However, improvement is not reduced to a stable sequence of types of private goods, taken in its repeating moments.

In addition to this repeating multiplicity, there is also order, which gives it stability. Basically, it implies: 1) the ordering of operations, due to which they represent moments of cooperation and ensure the repeating character of all truly desired moments of private good; 2) the interdependence of effective desires or decisions, coupled with their proper implementation by cooperating individuals16.

It should be emphasized that landscaping is not a utopian project, not a speculative ideal, not a set of ethical commandments, not a legal code

16 For a general diagram of such relationships, see: Insight, “Op emergent probabi-lity,” pp. 115-128.

"and not a super-institution. Landscaping is quite concrete: it is an actually functioning or non-functioning set of relations of the “if... then...” type - relations that guide operators and coordinate operations. It serves as the basis for repeatability I or non-repeatability , due to which any moments of private good are reproduced or not reproduced. Well-being is based on institutions, but is a product of much more: all the skills and abilities, all the efforts and ingenuity, all the hard work and mutual understanding of the people as a whole, which adapts to any change in circumstances, picks up any new undertaking, fights any trends leading to chaos17.

This leaves a third set of terms: freedom, orientation, revision, personal relationships and internal values. Freedom, of course, does not mean absence of determination, but self-determination. Any individual or group action is nothing more than a limited good, and, being limited, it is open to criticism. It has its alternatives, its limits, its risks, its obstacles. Accordingly, the process of deliberation and evaluation in itself is not decisive. We experience our freedom as an active belief in ourselves on the part of the subject, who completes the process of deliberation by choosing one of possible ways action and the transition to its practical implementation. It is to the extent that this self-belief regularly chooses not just apparent but true good that the self achieves moral self-transcendence: it lives an authentic life, constitutes itself as a generative value and creates final values: well-being, which is true good, and moments of private good, which are also true goods. On the other hand, to the extent that a person's decisions are mainly determined by his own motives, failure in self-transcending, in truly human existence, in generating value in himself and in his society is due not to the values in question, but to an incorrect assessment corresponding pleasures and pains.

Freedom is realized within the matrix of personal relationships.

17 For more information about this, see the book /i «^y/: about landscaping - p. 596, about common sense - pp. 173-181; 207-216; about faith - pp. 703-718, about banks - pp. 218-242.

In a community based on cooperation, individuals are connected to each other by their needs and the common welfare that suits their needs. They are bound to each other by freely assumed mutual obligations and the expectations that arise from them; they are connected to each other by the roles they have assumed and the tasks that must be accomplished. Normally, these relationships are animated by feelings. There are unanimous or opposing feelings regarding certain qualitative values or preference scales. There are mutual feelings when one responds to the other as some kind of optical value or source of satisfaction. Behind the feelings is the very substance of community. People are united by common experience, commonality or complementarity of insights, similarity of judgments about facts and values, similarity of life guidelines. People are disconnected, alien and hostile to each other when they lose contact with each other, when they do not understand each other, when they judge the same thing differently, when they choose opposing social goals. Thus, personal relationships range from intimacy to neglect, from love to exploitation, from respect to disdain, from friendliness to hostility. They either bind the community together, or divide it into parts, pulling it in different directions18.

Internal values are chosen values: true moments of private good, true well-being, a true scale of preferences in relation to values and methods of satisfaction. Correlating with internal values are the generating values that make choices: these are genuine individuals who achieve self-transcendence through acts the right choice. Since man is capable of knowing and choosing authenticity and

18 On interpersonal relationships as ongoing processes, see Hegel, Phenomenology of the Spirit, on the dialectic of master and slave, and Gaston Fessard, De l'actualite historique, Paris: Desclee de Brouwer, 1960, vol. I, which deals with the parallel dialectic of the Jew and the Greek. The issue is considered much more specifically in: Rosemary Haughton, The Transformation of Man: A Study of Conversion and Community, London: G. Chapman, and Springfield, III: Templegate, 1967. Description of interpersonal relationships, their technique and some theoretical For considerations, see Carl Rogers, On Becoming a Person, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

self-transcendence, to the extent that generative and internal values can coincide. When each member of a community strives for authenticity in himself and, to the extent possible, contributes to this in Others, then the generative values - those that make the choice - and the final values that serve as the object of choice, correspond to each other and are intertwined with each other.

Now we would have to talk about the orientation of the community as a whole. But for the moment we are concerned with the orientation of the individual within the oriented community. This orientation is rooted in transcendental ideas that demand from us the ability and endow us with the ability to advance in comprehension, to judge truth, to live up to values. But this opportunity and this requirement become effective only through development. A person must acquire skills and knowledge from someone else competent in a particular occupation. Man must grow in sensitivity to and conformity with values if he is to possess a truly human nature. But development is not an inevitable necessity, and therefore its results may be different. There are losers and mediocrity. And there are also those who tirelessly develop and grow throughout their lives. Their achievements vary according to their background, their opportunities in life, their luck in avoiding pitfalls and failures, and the absence of obstacles in their progress19.

If orientation is, so to speak, the direction of development, then revision is a change of direction, and a change for the better. A person frees himself from the inauthentic. He grows in authenticity. Harmful, risky, deceptive satisfactions are discarded. Fears of discomfort, suffering, and deprivation no longer so easily lead him astray. Values are seen where they were not noticed before. The preference scale is shifting. Misconceptions, rationalizations, ideologies are crumbled and shattered, man opens up to things as they are and to man as he should be.

Are there mites in Pitsunda? Ticks in Abkhazia. Pitsunda pine grove

Are there mites in Pitsunda? Ticks in Abkhazia. Pitsunda pine grove Red viburnum (Viburnum opulus L

Red viburnum (Viburnum opulus L Nail Making Business How to Make Copper Nails

Nail Making Business How to Make Copper Nails Stone brazier: material features and manufacturing options

Stone brazier: material features and manufacturing options Blackroot medicinal cultivation

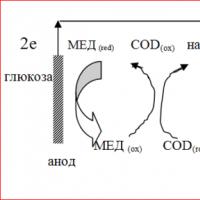

Blackroot medicinal cultivation Fuel cells: a glimpse into the future

Fuel cells: a glimpse into the future Houses with a hipped roof projects

Houses with a hipped roof projects